The election of Constantinos Karamanlis to the Presidency of the Republic on May 5, 1980 raised the question of replacing him not only in the prime ministership but also in the leadership of the New Democracy, which he had founded six years earlier. The competent body for the selection of the new leader, who would simultaneously be named prime minister, was the parliamentary group of the party. Two nominations were presented: on the one hand, Evangelos Averof-Tositsa, on the other hand, Georgios Rallis. Both were top officials of the New Republic, had a lot of experience, had been ministers for a long time (both before and after the dictatorship of the colonels), while they were in the close core of Karamanlis’ collaborators since the mid-1950s. In the vote that held on May 8, 1980, the winner was Rallis, who collected 88 votes against Averov’s 84, while three blank ballots were found. The defeat left Averov embittered, who felt that the result to his detriment had been partly (but certainly decisively) shaped by the behind-the-scenes support offered by Karamanlis to Ralli. His bitterness was expressed in his refusal to accept the vice-presidency of the government offered to him (although he had previously promised to do so in case he lost to Ralli). He was content to retain only the portfolio of Minister of National Defense.

Relations between Ralli and Averov were never fully restored. Rallis believed that Averov was constantly undermining him in order to replace him in the party presidency. The rivalry between them remained undiminished throughout Ralli’s prime ministership (May 1980 – October 1981). It did not soften even when in June 1981, that is to say in the final stretch towards the parliamentary elections, Averof assumed the position of vice-president in the Ralli government.

First clash the day after the defeat

The overwhelming defeat of New Democracy in the elections of October 18, 1981, which was just under 36% while PASOK triumphed with over 48%, was a strong blow for Ralli. The loss of the prime ministership was combined with the questioning of his position as party leader. At the last cabinet meeting of his government, held on October 19, Rallis came under fire from Averov, who attributed to him the main responsibility for the negative election result. From the very next day there were reports in the press describing Ralli’s stay in the leadership of New Democracy as doubtful. In order to clarify the situation, Rallis focused on asking the parliamentary group a question of confidence in his person. However, following the advice of Karamanlis (who argued that such an action was untimely, as the psychological imprint on the party officials from the electoral defeat was still very fresh) he decided not to do so.

The tension within New Democracy did not subside. Averov did not participate in the first post-election meeting of the party’s parliamentary group, which took place on October 23. Naturally, his absence fueled even more the rumors that sooner or later he would directly question Ralli’s replacement. Averov publicly assured that he would remain a “soldier of the faction”, the unity of which he was determined to preserve. But he added that he was equally determined to maintain “independence of opinion and action,” a statement that indirectly confirmed his leadership ambitions.

The parliamentary group votes against Ralli

Gradually, the challenge to Ralli’s face became more and more intense. It was obvious that the party had split in two: between those who supported Ralli and those who were friendly to Averov. The situation reached a tipping point when, a few weeks after the October 18th parliamentary elections, the elections for the staffing of the Steering Committee of the New Democracy took place. The process became the occasion of a new conflict between Ralli and Averof, with mutual accusations of trying to influence the result so that persons close to one or the other were elected. The two sides seemed to be taking positions for the final battle, which all indications were that it would not be long.

Under the pressure of the circumstances, at the end of November, Rallis announced that he would submit himself to the judgment of the New Democracy parliamentary group, which he would ask to renew its trust in him. He considered that, at the point where things had reached, this was the only solution. He could not continue to preside over a party in which he would not be recognized as the real leader. If voted down, he would step down as chief and pave the way for his succession. The crucial meeting of the parliamentary group was set for December 7.

As he had done immediately after the parliamentary elections in October, Karamanlis advised Ralli to avoid the vote of confidence because it would be conducted in the heat of the moment and there was a risk of creating major upheavals in the party. Concerned by the developments, on December 5 Karamanlis made a public statement. In it, after making it clear that he did not wish to get involved in any way in the issue of the leadership of the New Democracy, he emphasized that the main thing was to preserve the unity of the party. From circles close to Averov, Karamanlis’ statement was seen as indirectly reinforcing Ralli.

The result of the vote was overwhelmingly against Ralli. Sixty-one MPs of the New Democracy voted against him, 41 in favor of him, 9 preferred the white one, while one ballot was invalid. Ralli’s disapproval was unequivocal, as less than 2/5 of the caucus members sided with him. Apparently disappointed by the outcome, Rallis refused to accept the honorary presidency of the party, explaining that he was used to “bitter pills not being taken[ει] with a coating of sugar”.

The New Democracy in the vortex of introversion

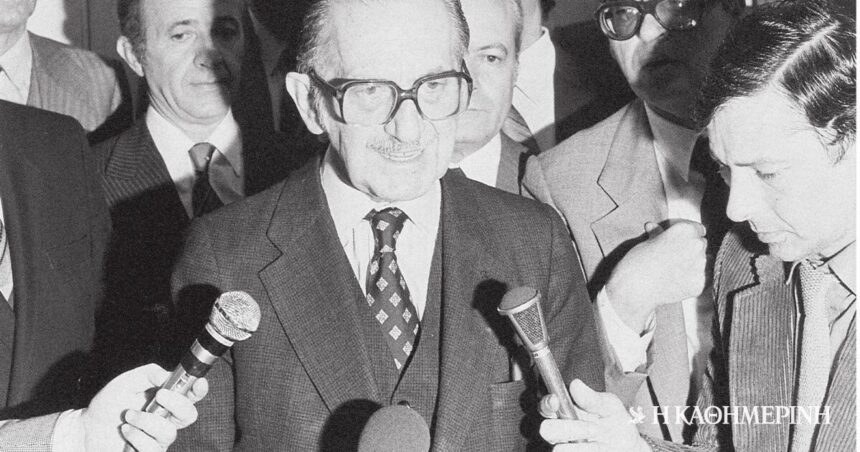

Two days later a new vote was held, this time to elect Ralli’s successor. Averof, Kostis Stephanopoulos and Ioannis Butos nominated themselves. As expected, Averov prevailed comfortably, collecting 67 votes, compared to 32 for Stephanopoulos and 12 for Boutou. Immediately after the process was completed, all three declared their unwavering commitment to the unity of the New Democracy and declared that they would follow a common path.

At the end of January 1982, Averov made a conciliatory gesture towards Ralli. He asked him to work together in order to exchange views on the future of the party. But Rallis did not respond positively. He accused Averof of having, from the very first moment, systematically undermined him in order to weaken his position as the leader of the New Democracy. Averov lifted the glove. He denied the accusations and countered that it was others who had undermined Ralli – without, however, naming them. He added that he had always expressed his thoughts and opinions openly, both privately at Ralli and publicly. The gap between Ralli and Averov remained unbridged.

Upon assuming the presidency of the New Democracy, Averof launched a tougher opposition line against the PASOK government, without, however, succeeding in practice in reversing the dynamics that had been reflected in the result of the parliamentary elections of 1981. At the same time, he made methodical efforts for the organizational reconstruction of New Democracy, laying the foundations for it to turn into a mass party. But he could not prevent the emergence of tendencies to question his leadership, which began to manifest themselves already in the first months of 1982, to intensify even more in December of the same year due to the shock of his health. New Democracy was still caught in the vortex of introversion, which it had entered after the departure of Karamanlis. Ultimately, Averov remained leader of New Democracy for only two and a half years, as he resigned after the party’s defeat in the European elections of 17 June 1984.

Mr. Antonis Klapsis is an assistant professor at the Department of Political Science and International Relations of the University of Peloponnese. His book “1974. Post-colonization” is published by Metaichmio publications.

Diligence: Evanthis Chatzivasiliou