June 1823 is a pivotal month in the history of Greek foreign policy. On June 6, Alexandros Mavrokordatos wrote the first letter to him George Canning. The second one followed on June 22. On the same day, he prepared letters to the Philhellenic Committee, other Britons, but above all the detailed instructions to the Greek envoys who would negotiate the loan in London. One could assume that on June 22, 1823, Greece was tied to the chariot of Great Britain. Not only did such a thing not happen, but Mavrokordatus wanted to avoid it at all costs. He was merely seeking to take advantage of the shift in British politics following Canning’s rise to the post of VP. Foreign. But in the instructions he set clear limits: relations with the British should be commercial and not exclusive; try to find out if Britain would accept our independence and with what borders; do not accept military aid, we only need financial.

Why did Mavrokordatus limit the discretion and negotiating leeway of the envoys in London? Why did he consider it wrong for the Greeks to be more closely associated with the largest empire on the planet? Not only because he was suspicious of the British but also for an additional reason. The political protagonist of the Revolution considered it dangerous for the Greeks to be involved in the rivalries of the European Powers. In the post-Napoleonic European security system, Greece did not have the margin for wrong moves, nor was it beneficial for a single power to monopolize its “protection” and economic relations.

The command

Mavrokordatus’ plan, however, was much more daring and far-sighted. He gave a clear mandate to the envoys to seek to establish relations with the US because such relations “really benefit Greece”. He asked them to meet and talk with the US ambassadors in London (Richard Rush) and Paris (Albert Gallatin), and even directly with the US Secretary of State (John Quincy Adams), with the discretion to negotiate everything with Americans, not just the terms of a loan. But he warned them: “While talks with the Americans are necessary, they will do us great harm if they are not carried out in the utmost secrecy.” One of the representatives (apparently his close associate, Andreas Louriotis) could, if he considered it appropriate, travel all the way to the USA. But he would have to convince the British that the only reason for the trip was to take out a loan.

On that day, June 22, 1823, Alexandros Mavrokordatos wrote another letter, the one he considered the most important. He was addressing the American sub. Foreign and future US president, John Quincy Adams. One cannot help but admire the way he approaches the Americans, essentially proposing an alliance: “Between the US and Greece, the geographical distance is enormous. But our Constitutions, as well as mutual interests, bring us so close.” Mavrokordatus attempted with one sentence to touch the two chords of Americans, the pragmatic and the idealistic, two chords born in the Jefferson-Hamilton conflict over the nature, historical role and vision of the new state; two chords that are visible to and today in American foreign policy.

Mavrokordatus had many reasons to be optimistic. President James Monroe had publicly spoken in favor of the Greeks in his address to the American Nation in late 1822. It was no accident. Andreas Louriotis had accomplished a small feat. During 1822 he met the US ambassadors, not only in London and Paris, but also in Madrid (John Forsythe) and Lisbon (Henry Dearborn). All of them were positive towards the Hellenic Struggle and sent similar reports to the sub. Foreign.

More positive was the American ambassador in Paris, Albert Gallatin, a former close associate of Jefferson and Madison. In April 1821 he had been personally informed by his close friend, General Lafayette. Lafayette, the hero of two revolutions, the American and the French, should be considered one of the most important Philhellenes of the period. Lafayette mobilized in favor of the Greeks in the spring of 1821 and did not stop his action until the end of the Revolution. Gallatin is the one who will receive from Adamantios Korais the appeal that Petrobeis Mavromichalis supposedly addressed to the American Nation. In fact (as the leading Greek historian of the period, Vassilis Panagiotopoulos, pointed out to me), the text was prepared in Paris by the envoy of Alexander Ypsilantis, Petros Ipitis. The Gallatin Archives in New York preserve the text in Greek and French, written in Korai’s own hand, as well as the copy received by Harvard professor Edward Everett. The text was published in translation in the Boston Daily Advertiser on 15.10.1821 and from there it was republished in dozens of newspapers. This Declaration is the revolutionary text that was used more than any other by the US Philhellenic committees that consistently pressured the US government to take a more active role in favor of the Greeks.

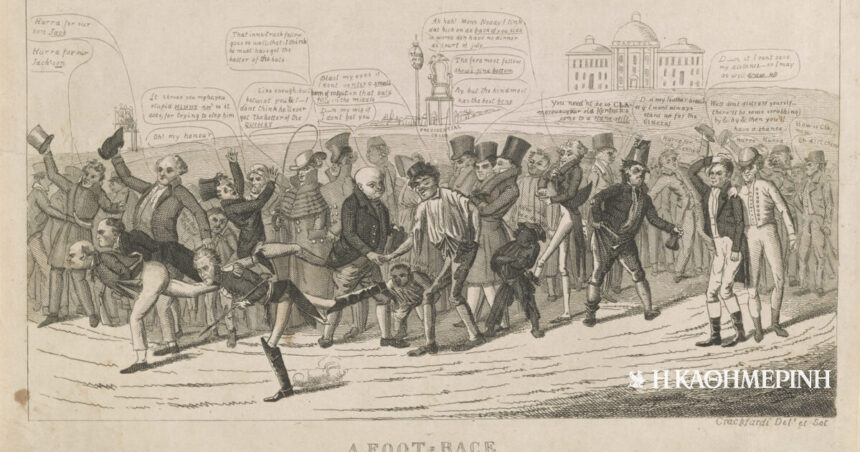

But the USA had already adopted the Monroe Doctrine, i.e. the doctrine of non-intervention in European affairs. The architect of this policy was John Quincy Adams who was now feeling the great pressure of the Philhellenes who were asking for an exception especially for the Greeks. Gallatin from Paris proposed, more or less, that the US Mediterranean Naval Squadron intervene on behalf of the Greeks. Russ, from London, forwarded Luriotis’ messages to the American leadership and played the role of intermediary in transferring money from the committees led by Everett to push in every direction with local parliaments, businessmen and intellectuals. The greatest pressure, however, came from Congressman Daniel Webster, a figure of standing and a possible candidate in the upcoming presidential election of 1824. In a series of meetings in the House of Representatives in January 1824, Webster asked the government to send a representative in Greece, effectively recognizing its international legal entity. Webster had a powerful ally, the Speaker of the House, Henry Clay. President Monroe himself, as his second term was coming to an end, seemed to be swayed and ready for something more decisive in favor of the Greeks. He addressed the still living founders and former presidents of the USA, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and John Adams (father of his minister). But while Madison and Adams encouraged him, Jefferson advised him to express only his sympathy for the Greeks and to avoid any violation of neutrality.

The ardent Philhellenes, the Monroe Doctrine and the role of Secretary of State John Quincy Adams, who was elected 6th president of the USA.

Thus, in the end, Adams convinced the president, not only to adhere to the doctrine of non-intervention, but also for the US to pursue an interstate trade agreement with the Ottomans.

But pressure from Webster and Everett forced the cabinet to discuss the matter in a meeting. Two ministers thought the US should make an exception to the Monroe Doctrine for the Greeks, but the pragmatic Adams showed them how dangerous that would be for US interests in the Mediterranean, especially as their ambassador in London had already arrived at a modus vivendi with Canning. Adams’ concern was not only about foreign policy but also about domestic policy. As he prepared to run for president he believed that Webster, Gallatin, Clay and other “frivolous philhellens” were ready to play the “Greek card” to gain publicity and popularity – as civil society in New York, in Boston, Philadelphia, had risen in favor of the Greeks.

But the worst happened to Adams just two months before the presidential election. In August 1824, Lafayette arrived in the USA, invited by Monroe to celebrate with the Americans the 50th anniversary of the War of Independence. Lafayette had planned to travel all over the United States and even with Gallatin in tow. Their tour, however, turned into a huge campaign in favor of the Greeks.

Half a turn

In the elections, Adams had to face three ambitious candidates who had supported the Greek cause in the cabinet or in the House (Clay). Of course the Greek question was not decisive for the election but one of those in which Adams was criticized, who did not receive a majority, neither in the electorate nor in the electors, and finally won the vote held in the House of Representatives, with the help of Clay – who was appointed secretary of state. Clay, who had so ardently defended the Greeks as Speaker of the House, attempted to slightly change US policy on the Greek question, in complete agreement with Adams. In September 1825 William Clark Somerville was appointed US representative to Greece. Somerville was no random person, he was friends with Lafayette, whom he would accompany on his return to Europe – a small gift from the American government to the French revolutionary. In the instructions prepared by Clay, the message to the Greeks was clear: “the people of the United States and their government, throughout the struggle of the Greeks, ardently desire that it should end in the freedom and independence of Greece. Don’t mistake our neutrality for indifference.” But Somerville fell ill on the journey to France and died at Lafayette Tower in Courpalais.

Alexandros Mavrokordatus, disappointed, now had only one option, to turn to Great Britain.

*Mr. Aristidis Hatzis is professor and director of the Laboratory of Political and Institutional Theory and History of Ideas at the University of Athens. He especially thanks the staff of the US National Archives and the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress for their valuable research assistance.