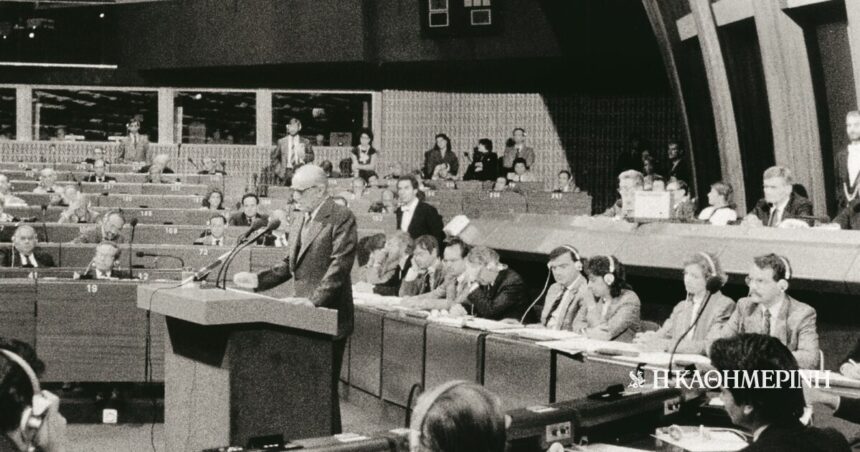

On September 15, 1983, Konstantinos Karamanlis became the first head of state of a member state of the European Communities to be invited to address the Plenary of the European Parliament. It was an important moment for the European Parliament, which had first been elected by popular vote in 1979 (the next European elections were held in 1984) and claimed a new role in the institutional system of European integration. This first directly elected European Parliament invited the president of the Hellenic Republic to address the Plenary.

Of course, it was also a great honor for Greece and personally for Karamanlis, who was recognized as an important figure in the movement for European integration. The “fathers of Europe” (Paul-Henri Spaak, Robert Schumann, Jean Monet, Konrad Adenauer) no longer existed, while the great figure of Jacques Delors had not yet emerged in European institutions. Thus, Karamanlis was called to the Plenary as a “Nestor” of unification and as a European symbol: he was the leader who had restored Democracy in his country causing international admiration, he had shown practically and strongly that he trusted the stabilization and protection of the young of Greek democracy in European institutions, and was distinguished for his impetuous as well as sober support for unification, on an ideological and practical level.

The political situation

The situation was indicative, both at the European level and at the Greek level. The institutions of European integration had gone through the multiple difficulties (and periods of economic depression) of the 1970s to the early 1980s. They were now looking for a new impetus for the great common cause, which they were to find with the Single European Act in 1985-86 under the guidance of Jacques Delors. In 1983, however, there was a sense of gridlock and a need for a new perspective. In this context, Karamanlis, internationally recognized as a dedicated servant of unification, was invited.

“I welcome the presence among us of one who has the great privilege of having corrected a profound falsification of History,” said the body’s president, Peter Dankert.

But also in the Greek context, the presence of Karamanlis in Strasbourg had interesting ramifications. In the summer of 1983, the PASOK government had taken two steps of enormous importance: it had accepted the European response to the Greek “memorandum” of 1982, which meant that it now definitively accepted the country’s status as a member state of the European Communities. Also, he had concluded the agreement for the stay of the American bases in Greece. Today, historiography points to the catalytic nature of these decisions of Andreas Papandreou, which created a consensus regarding the international orientation of the country and its status as a member of the West. But this is something we “see” today, safe in the knowledge of later developments. Then, the picture that was created was more confused.

Papandreou’s tactics

Andreas Papandreou had a tendency to make foreign policy with an eye on the “gallery”, i.e. on the domestic political reality, and thus he tried in every way to balance in his public opinion the feeling that he had “compromised” with the Americans. The result was, from August 1983, Greece to distance itself from a series of serious Western policies: proposal of Andr. Papandreou for a six-month postponement of the installation of the American “Euro-missiles”, at a moment of great psychological tension on the subject, a proposal that deeply disturbed other Western countries, but was repeated during the meeting of the Foreign Ministers of the Communities in Athens on September 12; distancing Greece from the Western policy on the Polish issue, at the same session; Greece’s distancing, at the same session, from the Western stance on the issue of the downing of the South Korean passenger plane (Jumbo) by the Soviet air force, which also led to the inability of the session to condemn the Soviet energy. It is worth noting that Greece held the presidency of the European Communities in 1983, therefore it had increased institutional obligations, and its attitude was treated in the most negative way by its partners. The West German Foreign Minister, Hans-Dietrich Genser, said that the Greek attitude was creating a “crisis of confidence” in the Community, while the European Parliament itself disapproved with its resolution the Greek government’s position on the issue of the South Korean aircraft.

Papandreou felt he needed to make these distinctions for the sake of his domestic political audience. The distancing was, of course, rhetorical, while the disagreements with Western policies did not concern issues of Greek interest. However, they were matters of great interest to other Westerners, who felt themselves harmed by Greek politics. Of course, the invitation to Karamanlis to address the European Parliament had been extended before this barrage of rhetorical distancing of Papandreou from the West. It was, however, Karamanlis’ speech at the European Parliament, and an opportunity to present the “other version” of Greek attitudes and positions, that is to say, the pre-eminently pro-Western one.

The ultimate goal is the political unification of Europe

Addressing the President of the Hellenic Republic, the President of the European Parliament, Peter Dankert, welcomed him as a great European figure and referred to the achievement of the restoration of Democracy in Greece: “I welcome the presence among us of him who has the great privilege of having correct a deep falsification of History”.

Karamanlis developed his positions, as he said, “more as a person who believes deeply in the European Idea and less as a carrier of the thoughts of the country I represent”. Karamanlis’ positions on this issue – in which the influence of the ideas of Constantinos Tsatsos is also evident – could easily, in today’s terms, be characterized as federalist.

Referring to the contribution of the Greek spirit to the European idea (but also to the ongoing drama of Cyprus), Karamanlis immediately posed the basic question in simple and clear terms: “Do we or do we not want the union of Europe?”. He emphasized that he did not intend to speak about current issues such as the increase in the Communities’ own resources or agricultural policy. He would talk about the big ones: “My intention is to encourage the unifying movement, proving the necessity of the Union.” He underlined that certainly the economic advantages of unification were a strong motivation, but also that the goal of political unification had been set from the beginning: “Because, if the Community’s ultimate goal was not the Union, we would not have created the Community and above all the This Parliament, which symbolizes and embodies unity”. However, the “asymmetrical promotion of economic over political goals” clouded the picture. The time had come to continue the march from the “partial” to the “total” and the pursuit of the Union. The European Communities, Karamanlis continued, secured peace and security in Old Epirus. But this was a stage towards union, not the end – he even quoted Montesquieu’s saying, “L’Europe n’est plus qu’une nation composée de plusieurs”. And he emphasized with emphasis: “Knowledge of the ultimate goal will make it possible to approach it safely and quickly.”

Criticism of the skeptics

In this context, he criticized the influence of “nationalist prejudices” and “selfish calculations”, which were blocking the way. The skeptics failed to perceive the message of the times and, as he said, were missing the forest for the trees: “Isolationism, tariff walls and unachievable self-sufficiency are historically outdated stages of economic and political action and are a passive response to events. […] The concerns of these skeptics are obviously due to confusion. Seduced by the differences of the surface, they do not see the unity of the depth. They do not see the common interests and risks that bind Europeans. They forget their common cultural tradition. The kinship of their morals. And the identity of their thought forms”.

The European countries, Karamanlis continued, could not cope with the challenges of the modern world by themselves, and it was necessary to speed up the path towards political unification. It was a choice between progress and regression. This is why the need for adjustments had to be realized. The delay in consolidation even weighed on financial performance. It was necessary to achieve monetary union. The institutions of the Communities were competitive and weak, while there was always the danger that the intergovernmental sector would become a lever to serve narrower national than European interests. But the European project could not be stopped: “Maybe the reactionaries will fight it. Skeptics may slow it down. However, they cannot thwart it, because it is, as I said, a historical imperative.” Karamanlis, therefore, favored a flight forward. He represented enlightened Greek Europeanism. But at the same time he spoke as a representative not only of his country but of an entire culture, the European one. During his speech, he was interrupted several times by the applause of the MEPs.

Mr. Evanthis Hatzivasiliou is a professor at the Department of History and Archeology of the University of Athens, secretary general of the Foundation of the Parliament for Parliamentaryism and Democracy.

__________________________________________________________________________________________

Main photo: 15.9.1983. In his speech to the European Parliament, Konstantinos Karamanlis represented enlightened Greek Europeanism. [ΙΔΡΥΜΑ ΚΩΝΣΤΑΝΤΙΝΟΣ Γ. ΚΑΡΑΜΑΝΛΗΣ]