We have learned to think about the aNaval Mediterranean as a neighboring region of the world sealed by instability and competition. But it wasn’t, and it’s not, only that. It was also a place for the development of an extensive ecosystem of different and dynamic communities that co -existed – not always harmoniously – different cultures, languages and religions. In this mosaic of polyethnic coexistence there were radiant Greek communities: in ports and cities such as Alexandria, Cairo, Constantinople and Smyrna.

THE DAYS, THE TRADE RELATIONS, THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEMS,

FAMILY DOCUMENTS AND PHOTOGRAPHS IMPROVED Moments of a LIFE now belonging to History.

The Greek Historical Archives of the Eastern Mediterranean They are a new research and archival initiative to highlight their history during the 19th and 20th centuries. Not through heroic narratives, but through the flow of everyday life: commercial relationships, education systems, family documents and photos that have captured the moments of a life that belongs to history.

These small and often unexplored aspects of daily life highlight not a “one -dimensional Greek world”, but the complexity and diversity of Hellenism in the Eastern Mediterranean. Behind ELIAMs are three scientists: the historian Alexanderthe historian Angel Dalahanis who also had the original idea, and the visual anthropologist Irene Chrysocher. The three share a common vision: the rescue and promotion of this precious piece of Greek – and not only – history. For this reason, they asked Egyptians, Asia Minor and other Greeks who came, lived or still live in the Middle East to allow them to photograph historical evidence in their homes.

Scouts of Suez on wheeled platform, 1940s, Suez. © private collection of goldsmith

As Irene Chrysochiris, a Doctor of Goldsmiths University of London, describes, “so far we have come into contact with 15 families through personal acquaintances. Most of the time the material they have are photos, documents and trifles stored in a drawer, a closet. Sometimes it is clear that the documents, photos and objects remained untouched, that is, they were in the same packages as they were transported by the arrival of families in Greece. “

Documents, photos and objects were left untouched, in the same packaging with which they were transferred to Greece.

This care reveals more than the value of the objects itself. It shows people’s desire to maintain a bond, emotional and psychic, with the past. This awareness dictates to ELIAM a relationship of trust and cooperation with families who want to share this story and make it visible in the public sphere.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a4ibnnp_4te

Easter celebration and children’s parties at the house and garden of Villa Kazoulis in Alexandria. Family excursions to the late 1940s.

The procedure includes the selection, photographing or digitizing personal documents such as photos, films, correspondence and other objects. As Alexander Kitroev notes, Haverford College’s History Emeritus Professor of History, “For the time being the material comes mainly from Alexandria and Cairo but there are plans to integrate material from other cities: Constantinople, Tanta, Ismailia, Jerusalem. It is also known that there was a significant Greek presence in Syria until the recent war there. We hope that we will cover the largest possible number, from Egypt to today’s Turkey“

Women pack cigarettes in boxes at the Papatheologou Cigarette Factory (Tabacs & Cigarets Papatheologou Société Anonyme), 1920s, Alexandria. © Private Capaitzi Collection

The photos, the mail

And the “old cards”

As Angelos Dalahanis, a major researcher at the National Scientific Research Center of France (CNRS), explains, the group’s many years of research on the Greek presence in the Eastern Mediterranean highlighted two key issues, one practical and one epistemological. “The minutes is about the lack of sensitivity or knowledge that often exists about what to do ‘old’ personal and family documents, photos and other historical evidence. Researchers are often witnessed by mismanagement of these precious evidence whether they are photographic albums, correspondence or other “old cards” that often end up in a trash can after some relocation or any other reason. “

These films have a special value for us, not only because they record simple family moments, but mainly because of their rarity.

Analyzing the epistemological issue, Mr Dalahanis adds: “The epistemological issue relates to what kind of humanities we are interested in. If we want to think about people’s daily lives we need access to archival material (photographs, documents, films, interviews, etc.) that captures these experiences. This material is not necessarily found in institutional organized records but in the homes of people in Greece, in Egypt and elsewhere. “

ENOA rowing team after a race, 1966, Alexandria. © Private Collection Archoleka

Among the evidence that ELIAM has collected, some stand out for their uniqueness and emotional value. One such example is a series of Super 8 film, which were stacked in a box, ready to fly. As Irene Chrysocher describes: “These films are of great value to us, not only because they record simple family moments, but mainly because of their rarity. It is well known that such materials were limited availability, as film machines had high costs and were mainly a privilege of wealthy families. “

Ms. Irene, today, 99, told us the story of her life, which includes her childhood in Kaso until the age of 11, the years she lived in Ismail from 1937 to 1962, as well as her period Her stay in Athens for 10 years before returning to Kaso in 1972.

Another moving story is that of Irene Sakellis, which they met in Kaso. As the visual anthropologist tells: “Mrs. Irene, now 99, told us the story of her life, which includes her childhood in Kaso until the age of 11, the years she lived in Ismailia from 1937 to the 1962, as well as during her stay in Athens for 10 years before returning to Kaso in 1972. Its routes cover the Eastern Mediterranean in a long time and such testimonies are valuable, for as many years we can still have them. “

Tugboat race during school races, 1952, Alexandria. © Katsimbri Private Collection

Uniting communities

Life in the Greek communities of the Eastern Mediterranean was not limited to family daily life, as public activities and community institutions played an important role in creating links and cultivating the sense of “belonging”. As Alexander Kithanev notes: “We also see the role of some institutions and processes that have not been studied as much as they should and are key to understanding the Greek experience: scouting, sports, charity.”

Going, for example, to archaeological sites in Ano Egypt or the dams in the Nile, we include a closer relationship with the places where the Greeks live.

These activities are offered to think about the past and to understand the mechanisms of constitution of Greekness. School and family excursions, for example, were more than simple trips. Mr Kithanev explains: “A presumption that is common in many personal collections are photos of excursions, either school or family. It is seemingly less important than other processes, but it appears as an activity in other Greek communities in other parts of the world and among other ethnic groups. Going, for example to the archaeological sites in Ano Egypt or the dams in the Nile, we include a closer relationship with the places where the Greeks live. “

Visit to the Archaeological Museum of Cairo, 1962, Cairo. © private collection of Avramidou

The complexity of Greek identity

The evidence of ELIAM gathering the variety of experiences and the liquidity of Greek identity in the Eastern Mediterranean. As Angelos Dalahanis points out: “We see that there was no one -dimensional Greek world but many Greek worlds.” These “many worlds” are reflected in the stories and evidence that ELIAM records. For example, as Mr Dalahanis explains, “Egyptians are not only the wealthy Alexandrians. Asia Minor are not just those who lived in Smyrna. Also, private historical evidence put Greeks/Greeks/Greeks who were not necessarily Christian Orthodox, who did not have Greek citizenship or may not have spoken Greek. “

Egyptians are not only Alexandrians. Asia Minor are not only those who lived in Smyrna.

This complexity raises critical questions: “Overall our material pushes us to question what it means to be a Greek/Greek woman in the 19th and 20th centuries.” Alexander Kithanef adds through specific examples: “In everyday life, events are experienced by everyone and each in a different way. Everyone can be considered Greeks, but one will go to a Greek school, the other to a foreign language, others work in a Greek business, others in local or European, all of which produce a multifaceted and rich life experience worth recording. “

Woman with a child poses overlooking the area, 1965, Constantinople. © Private Baller Collection

Many of the narratives that Eliam gather are focusing on the nostalgia for the daily lives of these communities. The life they describe is full of images of relationships, moments and conditions that belong to the past. Mr Kithanev says: “A common motif we have observed during the collection of these stories, which come mainly from Egypt, is the intense nostalgia for life there. Families’ narratives often describe this period as a golden age, with memories of everyday life, social relationships and conditions in the region. “

THE MATERIAL leads us to think differently the Greek presence in the EAST MEDITERRANEAN: with terms of real life and not mythology.

These evidence and stories, however, invite us to finally approach history free of stereotypes and focusing on abstract shapes. Or as Angelos Dalahanis rightly observes, “the material leads us to think of the Greek presence in the Eastern Mediterranean differently: in terms of real life rather than mythology.”

The first public presentation of the website of the Greek Historical Archives of the Eastern Mediterranean (eliam.gr) takes place on Thursday, February 6, 2025, at 6.30 pm, at the Cultural Center of the Municipality of Athens (Akadimia 50, Athens 106 79).

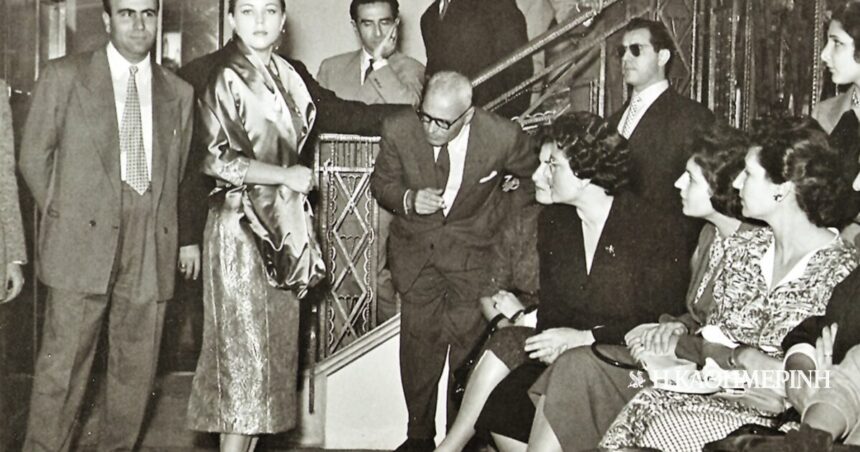

Central photo: Fashion show at the SALONVERT fabric store, 1950s, Alexandria. © Private Sideri Collection