On February 11, 1825 started at southwestern Peloponnese or landing of Egyptian regular armyled by Ibrahim Pasha. Within 14 months, Ibrahim will reverse almost all the Greek successes of the period 1821-1823. It will crush him Karaiskakis and him Javella in Kremmidi on April 7th and a few days later he will manage to fully control Navarino Bay. On May 20, Mr Papaflessas will sacrifice himself in Maniaki, while at the beginning of June o Theodoros Kolokotronis will be defeated in Trambala.

When Kolokotronis realized that he would not be able to intercept Ibrahim easily, he ordered the evacuation of Tripolitsa. His assistant, Fotakos Chrysanthopoulosdescribes in an evocative manner in his memoirs the retreat of the Greeks and the burning of Tripolitsa, so that it would not fall into the hands of the Egyptians: “The city was deserted, I only saw houses burning. As I moved towards the center of the city, I grew wild, scared. On the road I saw only corpses and figures of people loaded with things and speeding away while the dogs howled. I immediately left Tripolitsa without carrying out the orders of the leader.” Nothing seemed to be able to prevent Ibrahim from advancing to the plain of Argos and besieging Nafplion.

In the chaos o Makrigiannis he managed to keep his composure. It was fortified at Mylos to protect Nafplion and the supplies that the government had collected for Kolokotronis. They arrived to reinforce him Dimitrios Ypsilantis and the Konstantinos Mavromichalis. The three of them achieved the only major victory there against Ibrahim, on June 13, 1825. However, a few days later, Kolokotronis lost another important battle in Trikorfa and then realized that the only weapon he had left was guerrilla warfare. Ibrahim had on his staff experienced French and Italian officers, fought with tactics that surprised the Greek commanders who were now paying dearly for the systematic undermining of the regular army organization. On December 12, the Egyptians, who had now brought most of the Peloponnese under their control, were encamping outside Messolonghi. The countdown had begun for Roumeli as well.

Two advantages

These tragic events would probably have led to her end Revolution if the Greeks did not have two important advantages. The Eastern Mediterranean was controlled by his national fleet Andreas Miaoulisbut mainly from the unruly Greek corsairs and pirates who had destroyed the trade. On the other hand, his brilliant foreign policy had already begun to pay off Alexandrou Mavrokordatos which, aiming at the internationalization of the Greek issue, obliged the European Powers to mobilize. At the end of 1824 the Russian Emperor Alexander I had almost decided to invade the Ottoman Empire, at the same time that the Egyptian troops were preparing to land on the Morea. Alexander’s sudden death did not change the situation as his successor and brother Nicholas was determined to pursue a harsher policy towards the Ottomans, although he was hostile to the Revolution. The British and Austrians wanted to prevent a Russo-Turkish war that would allow the Russians to control the Balkans, while France was playing a double game: cooperating with the Egyptians and promoting a French prince for the Greek throne at the same time.

The Greeks flirted with the French attack of friendship, hoped for British mediation, even talked with the Austrians and sought to avoid the Russian plan which would lead instead of national independence to autonomy with servitude to the Sultan and the long arm of Russia controlling the weak Greek hegemony. Mavrokordatos insisted that only the alliance with the USA would ensure the national independence of Greece. He believed that the Greeks should avoid the monopolization of their protection by a European power.

However, Ibrahim’s advance led to the acceptance of a plan established in Zakynthos by a group of Greek patriots (the so-called “Zakynthos Committee”), which had privileged relations with the British administration in Ionia and the tectonic networks. Count Dionysios Romas, Panagiotis Stefanou and Konstantinos Dragonas prepared the first version of the Petition for Protection which was derogatorily named “Deed of Subordination”. The Greeks placed their hopes in Great Britain and entrusted it to undertake the protection of their interests: “The Greek Nation, by virtue of this act, voluntarily places the sacred legacy of its Freedom, National independence and Political existence under the sole defense of of Great Britain”. In the excellent monograph of H.N. Vlachopoulos entitled “Dionysios Romas and the Zakynthos Committee on the road to national formation” (EKPA, Sharipoulos Library, 2020) readers will find a reliable detailed description of the preparation of the text.

The desperate Kolokotronis explains why the help of the Europeans was necessary in his (unpublished) report to the Government (7.9.1825): “Horrible indiscipline, horrible disorder, more horrible desertion. These are the unique virtues of our army…”.

The four versions

British Foreign Secretary George Canning received four versions of the Petition with different signatures from “the Clergy, Parliamentarians, Politicians and Military Chiefs on Land and Sea of the Hellenic Nation”. The first (30.6.1825) is signed by Theodoros Kolokotronis and the most important Peloponnesian chieftains and provosts; the second (10.7.1825) is signed by Andreas Miaoulis and the important factors of Hydra, Spetses and other islands; the third (Athens, 14.7. 1825) signed mainly by Roumeliotes; h fourth (26.7.1824) is again signed by Miaoulis, supposedly in Messolonghi for symbolic reasons, and includes chieftains, clergy, provosts and politicians of western Roumeli. There we find the names of Alexandros Mavrokordatos and his team (Trikoupis, Polyzoidis, etc.) who delayed signing as the Zakynthos Committee tried to exclude them. In the British National Archives where I found the original texts, the British added a letter from Kolokotronis to Canning (which was prepared in Zakynthos), an identical one from Miaoulis, a common one between the two but also an individual letter-accession from Georgios Kountouriotis, president of Executive. The file closes with Canning’s reply to Kolokotronis and Miaoulis.

Mavrokordatos, though marginalized, saw to it that the appeal was formally approved by the constitutional organs of the Greek revolutionary state, and shortly afterwards sent Canning one of those letters of his which show his impressive diplomatic skills. He said, almost openly, to the British minister that the Greeks would trust Great Britain as long as it helped them effectively, otherwise they would turn to another Power.

Canning did not answer to the government, nor directly to Mavrokordatos, but exclusively to Kolokotronis and Miaoulis – the British did not officially recognize the Greek revolutionary state but had recognized the revolutionaries as “belligerents”. Despite Mavrokordatus’ concern, the Request for Protection ultimately benefited the Revolution’s diplomatic position as it gave Canning the leverage he was looking for in his negotiations with Russia and the Ottoman Empire and facilitated his strategy which was (as evidenced by numerous , hitherto unknown documents which I had the opportunity to study in the British archives): The British were ready to recognize, even unilaterally, the national independence of the Greeks as long as the Greeks managed to win it on their own, on the battlefield. If the Greeks did not succeed militarily but endured, even with heavy losses (as happened during the period 1825-1827), the British would force a compromise with the Porte, even in a forceful way, but definitely in cooperation with Russia and France so that no power could take advantage of the intervention.

The “reversal of defeat”

Much has been written about the Protection Application in the context of demagogic, poor quality, historiography. It is hard to accept that the Revolution was in decline, almost everything had fallen apart and the only way to save it was through the tools of diplomacy. The resilience and stubbornness of the Greeks allowed them to achieve, finally, the “reversal of the defeat” (in the successful formulation of Petros Pizania), but with the help of the Europeans. The desperate Kolokotronis explains why this was necessary in his (unpublished) report to the Government (7.9.1825): “Horrible indiscipline, horrible disorder, more horrible desertion. These are the unique virtues of our army. They would all be happy if they never heard an order from a superior. The only thing that pleases them is to go here and there robbing their Christian brothers, hunting them down to rob them in their villages, even in their hiding holes. And if the army has to move on some mission then they disappear with countless pretexts. Whether you have them or not, it does the same.”

These phenomena forced the Greek Administration to give permission to Kolokotronis to arrest, interrogate, try and execute the deserters within 24 hours. But the situation hardly improved. Until 1828 the disorderly Greek army had the same pathologies. As a result, Dimitrios Ypsilantis was forced to denounce in his (unpublished) report, in July 1828, some of the best-known chieftains of the Eastern Mainland: “Since they were children, they have been brought up with robbery and robbery, and they taught this abominable behavior to their soldiers; they were taught to be unfaithful and to commit obscenities. Please give me the right to remove them from the camp.”

When Messolonghi fell in April 1826, the Greeks decided to settle for a sui generis regime of autonomy if it freed them completely from the presence of the Ottomans and protected them from the embrace of Russia. National Independence now seemed an elusive dream. Kolokotronis wrote to his men on 21.4.1826: “Don’t worry, not everyone has abandoned us. We hope that the Christian forces will help us. Not, of course, as we would like, but as they themselves decide and as reality allows.”

At the beginning of January 1826, George Canning briefly described his political plan to the British ambassador in Paris: “I hope to save Greece by taking advantage of the fear which the Russians cause in the Turks, while at the same time avoiding a Russo-Turkish war.” He didn’t achieve the latter, but he achieved the former. But that is another story.

Mr. Aristides N. Hatzis is a professor at the University of Athens and author of the book “The Glorious Struggle: The Greek Revolution of 1821” (published by Papadopoulos, 2021). He especially thanks his collaborator Angeliki Diamantopoulos, as well as the National Archives of Great Britain for helping him in his research.

_______________________________________________________________________________

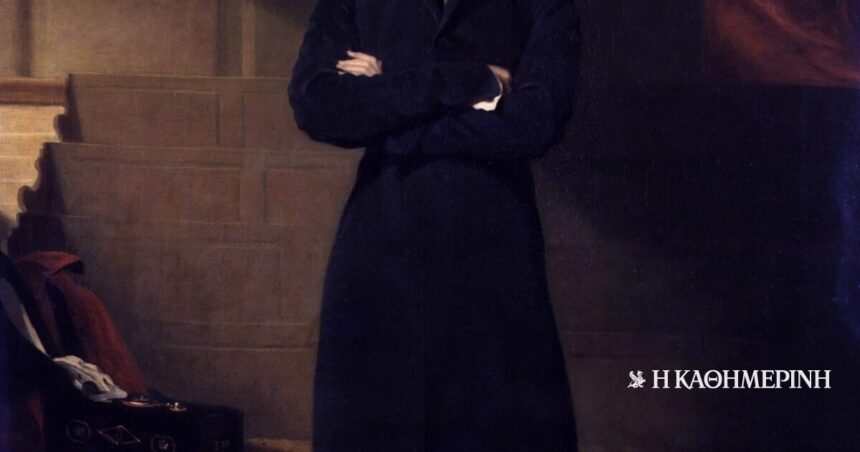

Center photo: George Canning in 1825 by Thomas Lawrence. At the beginning of January 1826, the Foreign Secretary of Great Britain succinctly described his political plan to the country’s ambassador in Paris: “I hope to save Greece by exploiting the fear which the Russians cause in the Turks, while at the same time avoiding a Russo-Turkish war.” He didn’t achieve the latter, but he achieved the former. [National Portrait Gallery, Λονδίνο]