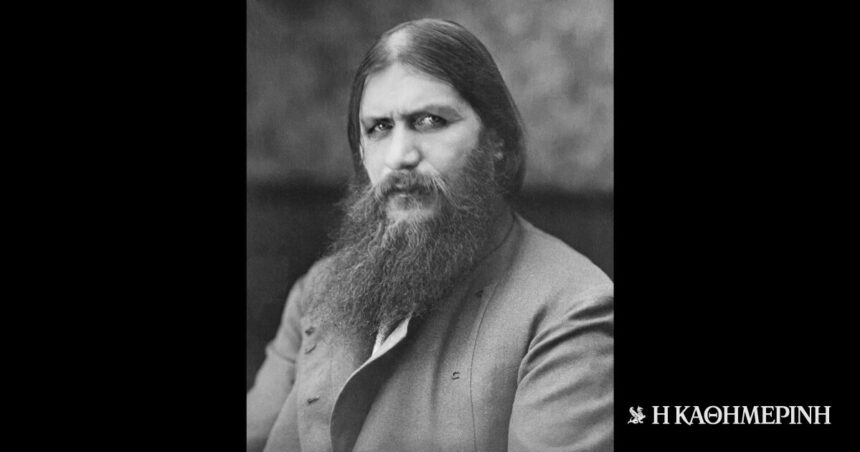

Grigory Rasputin, born in a village in Siberia, would already show a strong interest in religion as a teenager. Shortly thereafter, he would become a wandering religious, calling himself a mystic and healer. Information about Rasputin’s activity and charisma had begun to spread in Siberia as early as the early 1900s. A few years later, when he traveled to the city of Kazan, he became known for his ability to help people resolve their spiritual crises and to address their concerns.

With these rumors accompanying him, from 1906 onwards Rasputin would succeed in exerting great influence on the Imperial family, and especially on Tsarina Alexandra, who was convinced of his mystical healing abilities. She even believed that Rasputin could heal her son, Prince Alexei, who suffered from hemophilia.

When Tsar Nicholas left St. Petersburg to lead the Russian forces during World War I, it was Rasputin who effectively ruled the country through Alexandra, helping to further develop the already negative climate for the Romanov regime and charges of corruption and chaos. In the eyes of a large portion of public opinion he was a drunkard, who also indulged in debauchery. As the war continued, rumors circulated that he was a lover of the Tsarina. Other rumors spoke of a treacherous connection with Germany, of an attempt to spread a cholera epidemic in St. Petersburg with poisoned apples, and of his relations with the tsar’s young daughters.

Gradually, voices rose within the church and aristocracy to highlight the danger posed by Rasputin’s growing power, and the need to remove him by any means necessary became increasingly popular. So a group of nobles, led by Prince Felix Yusupov, husband of the tsar’s only niece, and Grand Duke Dimitri Pavlovich, the tsar’s first cousin, planned his execution.

On the night between 29 and 30 December 1916, Yusupov and Pavlovich lured Rasputin to the former’s palace on the Moika River in Saint Petersburg, giving him food and cyanide-laced wine. However, when they thought the poison didn’t work, they shot him point blank. Nevertheless, Rasputin remained alive and tried to escape. They shot him again and, while he was still alive, tied him up and threw him into the frozen Neva River. His body would be found several days later and his death would be attributed to drowning. Yusupov in his memoirs, which were published in 1928, spoke of the forces of evil, which did not allow his death.

The plotters of Rasputin’s assassination hoped that his removal would make Tsar Nicholas more receptive to the advice of the nobility and the legislative assembly, the Imperial Duma, in effect giving the monarchy one last chance. However, his assassination did not bring about any radical change in policy, and the whole situation would eventually lead to the Russian Revolution and the fall of the Romanov regime.

Column editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigoni-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis