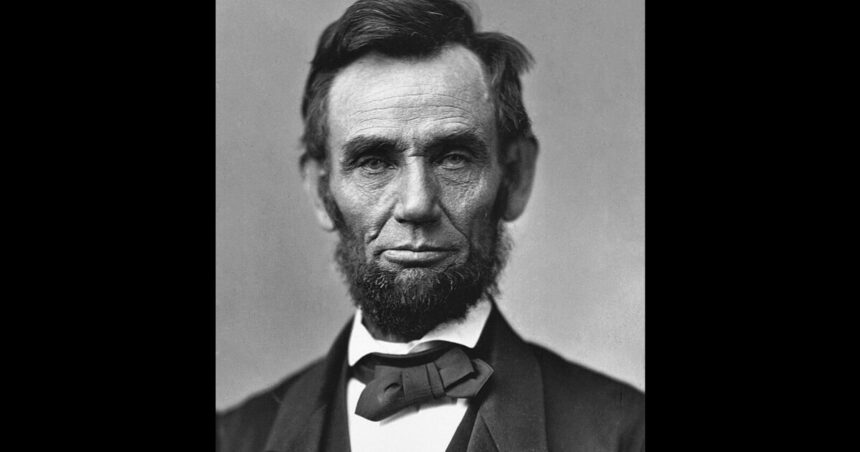

The Emancipation Proclamation, signed by Abraham Lincoln on January 1, 1863, is still one of the major milestones in the political and social history of the United States. It was the first step towards the final abolition of slavery, a shameful institution which contradicted the country’s liberal ideology. It largely marked a new beginning for the civil war-torn country, strengthening democratic principles and helping to modernize institutions. He thus laid the foundation for the creation of the political and economic miracle of the following decades.

The abolition of slavery in the United States, of course, was not an easy task nor was it accomplished in a short period of time. The third American president in a row, Thomas Jefferson, signed a law in 1807, which prohibited the importation of African slaves. By the end of his term in 1809, slavery had been virtually abolished in the Northern States. However, in the American South the situation was completely different. Slavery was largely an institution entrenched in the life of the Southern States. As a result of the Industrial Revolution, there had been an increased demand for cotton, an agricultural product that was grown in abundance on the fertile plains of the South, where tens of thousands of slaves worked.

Initially, the leader of the Republican Party, Abraham Lincoln, although he believed that slavery was a great evil for the United States, he did not share the opinion that it should be abolished necessarily, maintaining reservations about the conditions under which blacks and whites would coexist in the country. He was in favor of their settlement in areas outside the country. Therefore, in the election campaign of 1860 he did not include the abolition of slavery in his political program.

During the civil war, however, he changed his attitude. Believing that freeing the slaves would undermine the war efforts of the South, he decided to publish the Emancipation Proclamation. The Proclamation briefly provided for the liberation of the slaves in the areas which were under the control of the South. This measure, however, did not include four Southern States, which had remained loyal to the Federal Government of Washington, as well as some Southern territories, which were held by Northern troops. Nevertheless, he is considered to have made a decisive contribution to the subsequent emancipation of the slaves, when the Federal Government prevailed in the Civil War.

From the government’s side, the appropriate initiatives remained to be taken for the official institutionalization of the abolition of slavery in the country. In April 1864, the Senate voted in favor of the 13th Amendment, according to which “there shall exist in the United States, or in any territory under their control, neither slavery nor involuntary compulsion, except as a punishment for crime, for which the person concerned will have been legally convicted”. The passing of the Amendment, however, was delayed for many months in the House of Representatives. Ultimately, the 13th Amendment passed by a vote of 119 to 56 in a vote on January 31, 1865.

Although not required by the Constitution, the Joint Resolution of Congress was sent to the President for signature. Beneath the signatures of the presidents of both Houses of Congress, Lincoln wrote “Approved” and then affixed his signature. The diary read February 1, 1865. His assassination a few months later, in April 1865, deprived him of the joy of seeing the Amendment incorporated into the United States Constitution in December of that year.

Column editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigoni-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis