The evening of January 13, 1910 ushered in the end of an era dominated by telegraphs with their dots, evening papers, silent films, as well as the so-called “soapboxes”; that’s what the raised wooden platforms were called (originally used to send soap or other dry goods to retail stores) on which one climbed when one wished to deliver an impromptu public speech, often on a political subject. In its place, a new age would come, based on radio communications, which provided direct wireless communication between regions that were separated by a great distance.

Wireless telephony had already been created since the end of the 19th century. More specifically, innovative European scientists (including Heinrich Hertz, after whom the radio frequency unit is named) had contributed to this field by experimenting with electromagnetic waves. In the 1890s, Guglielmo Marconi invented the vertical antenna, which transmitted signals over an ever-increasing distance, eventually enabling in 1901 to send messages from England to the ‘New Land’ – communicationally ‘bridging’ the two sides of the Atlantic Ocean . Thanks in part to these advances, in December 1906 Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden was able to organize a holiday broadcast for operators off the Atlantic coast. The song and verse reading that followed was heard on ships from New England to Virginia.

In the decade following this broadcast, interest in radio technology grew. Amateur devotees became known as “fans” rather than “listeners”, used pejoratively to indicate that a person was not actively involved in both sides of the radio broadcast. At first there was a large portion of Americans who, because they did not understand radio and how it worked, were very wary. Various theories were put forward, from accusations that the radio with its electromagnetic waves was responsible for the creaking of the floorboards to it being responsible for causing nausea in children, difficulty in producing milk for cows or even causing drought!

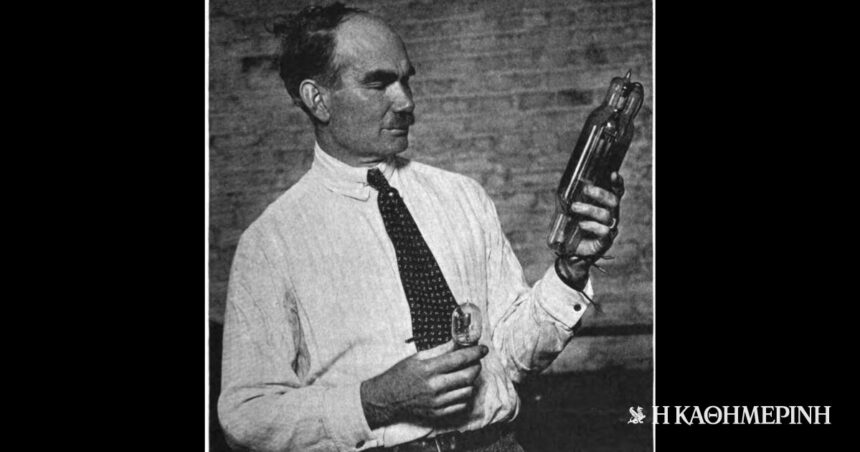

On January 13, 1910, tenor Enrico Caruso prepared to do something completely innovative for the time: he would make the first live radio broadcast. Inventor Lee de Forest had suspended microphones above the stage of the Metropolitan Opera and set up a transmitter and antenna. With the flip of a switch, the sound of Caruso’s voice would be “magically” transported from inside the opera house to multiple locations throughout New York. It was something unprecedented.

Soon, the medium of radio would boom. In the following decade it was already realized that radio was a much faster medium of information compared to the newspaper. Detroit’s experimental station 8MK announced the results of the 1920 presidential election to the approximately 500 residents who had receivers. In the USA, in 1922 28 stations were operating, reaching 1,400 within the next two years.

Although the Great Depression of 1929-33 slowed the growth of radio somewhat, it would not stop it. Radio, both in America and worldwide, was to become one of the most popular media in the first half of the 20th century, while it continues to be powerfully present to this day.

Column editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigoni-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis