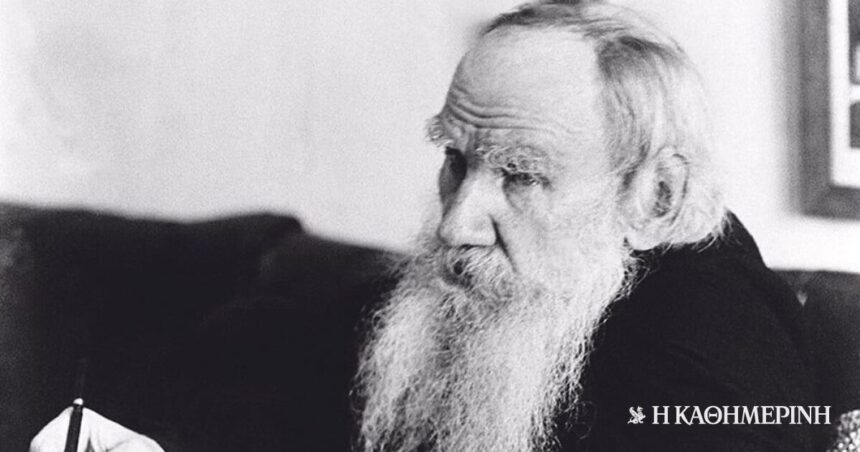

In November 1910, a small railway station in Astapovo, in the Lipetsk region of Russia, had attracted the attention of the entire country: the villagers, the journalists, and even the government. And this because there was old Leo Tolstoy, sick with pneumonia and confined to the station master’s lodging.

But the story was quite complicated. On October 28, the 82-year-old Tolstoy made a daring move: taking only a few personal belongings and his doctor, Dr. Makovitsky, he left his family estate, Yasnaya Polyana, leaving behind his wife, Sonya, and headed first for neighboring city of Tula.

The abandonment of the family home by someone who constantly spoke of love and the sanctity of marriage may surprise many, but in reality Tolstoy and Sonia’s married life was anything but happy, anymore. Tolstoy’s spiritual quests had led him to renounce all religion (and excommunicate himself from the Russian church) and all material goods. He had decided to renounce any privilege afforded him by his aristocratic descent (indeed he did farm work on the family estate) and to grant all rights to his works, whether published or not, for public use.

This attitude of Tolstoy had caused great friction with his wife Sonya, who believed that his fortune should remain in the hands of the family, which numbered a total of 23 children and grandchildren. For many years, the couple’s fights were daily and stormy. Tolstoy tried to exercise restraint, but did not always succeed, while Sonya felt increasingly excluded from her husband’s circle, as their children and his students—his “apostles,” as she called them— chiefly Chetkov’s assistant, they had taken his side and kept secrets from her – notably Tolstoy’s will granting rights to his works for public use. But since this could not be accepted in a Russian court, Tolstoy left all his property, movable and immovable, to his youngest daughter, Alexandra, who was also his trusted assistant.

In her diary, Sonya describes the reactions of Tolstoy’s “apostles” when she entered the same room: although she might find them laughing, as soon as they sensed her presence, they fell completely silent. On the other hand, Sonya’s behavior made the situation difficult, as she had “hysterical fits”, threatening to kill herself or kill her husband. In fact, in the days before he left her, Tolstoy wrote in his diary that she always left her bedroom door open and listened to his movements. When he left his unlocked and Sonia thought he had fallen asleep, she would go into his room rummaging through his papers and trying to find the key to his desk drawer where he kept his manuscripts.

On October 28, therefore, unable to continue living in Yasnaya Polyana with Sonia, he organized his escape, giving a letter to his daughter Alexandra about Sonia:

“My departure will grieve you. I am sorry for this, but please understand and believe that I could not do otherwise. My position at home is becoming unbearable. Apart from anything else, I can no longer live in the luxurious conditions in which I used to live, and I am doing what old men of my age usually do: I am leaving this worldly life to live out my last days in peace and solitude.

“Please try to understand and don’t follow me if you find out where I am. Your coming would worsen your position and mine and not change my decision. I thank you for the honest forty-eight years of your life with me and please forgive me for any wrong I have done towards you, as I forgive you with all my soul for all the harm you have done to me. I advise you to reconcile yourself to the new position in which my departure brings you, and to bear no ill feelings towards me. If you want to report something to me, give it to Sasha (Alexandra). He will know where I am and will convey to you whatever is necessary. But he can’t tell you where I am, because he’s promised me not to tell anyone.”

Starting his train journey, he was quickly noticed and within a short time, most of the villagers on the train had gathered in his carriage to meet the “great Tolstoy”. He talked with them about religion, taxation and politics, and later, exhausted by the journey, he contented himself with listening to their songs.

In fact, Tolstoy had not planned his trip in detail. He ended up in the monastery of Sarmontino, where his sister lived, and decided to head for Bulgaria. However, a cold that developed into pneumonia immobilized him, following the decision of his doctor, at Astapovo station.

Journalists, who had learned of his trip and were following his every move, as were some of the Tsar’s spies, sent urgent telegrams about Tolstoy’s condition to the newspapers and the government, respectively, creating a frenzy over the health of the “first Russian citizen ».

His condition steadily worsened, and his children rushed to his side. Although in one of his moments of mental clarity, he had asked Sonia not to come, she came and saw him while he was unconscious, asking him to forgive her.

Leo Tolstoy died on November 20, 1910 in the modest station master’s room at Astapovo station (now named after him). A crowd of villagers, which could not be restrained by the police, escorted the great writer to his last abode. It was his wish to have a non-denominational funeral and to be buried on the hill where he used to play as a child in his “bright glade”, Yasnaya Polyana.

Column editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigone-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis