In the 16th century there was a huge “explosion” in the amount of printed material available. In the first quarter of the following century, during the reign of James I (1603-1625), in addition to literary material of all kinds (speeches, poems, plays, ballads, satires), which continued to circulate and gain the interestingly, a growing “thirst” for knowledge was observed around them wars which raged on the mainland Europe. Its manifestation was the appearance of newsletters and forms, usually sent from London to the provinces.

However, the ever-increasing influence of the press and publications of all kinds worried both the Tudors and the Stuarts, who tried to control it, with the help of the bishops and the printers’ and booksellers’ guild, which was based in London. Expression of these efforts was that it was deemed necessary to grant permission from the guild before circulation of the forms (which excluded what was not deemed acceptable). It was also provided that offenders would be prosecuted on a case-by-case basis with severe penalties.

In 1625, Charles I succeeded James. In the decade that followed, William Lord, Archbishop of Canterbury and a close associate of Charles, used his court to counter criticism of the king’s policies in areas such as taxation, foreign affairs and the church. Among the prominent figures punished at the time was the lawyer William Prynne. For allegedly slandering Queen Erieta Maria (he had written that female actors were prostitutes, a phrase considered insulting to the queen), Prynn was punished by having his cheeks stamped and his ears cut off. In time, his mutilation became the subject of the press and was depicted in print.

As the struggle between Crown and Parliament intensified, the press became a vehicle of propaganda and manipulation.

In November 1640, the convocation of Parliament (which became known as the Long Parliament) offered an opportunity to lift this repressive measure. However, as the Long Parliament opposed Charles and the struggle between Crown and Parliament intensified, the The press evolved for both sides into a vehicle of propaganda and manipulation. Thus, in the spring of 1641, a permanent committee functioned, with the object of granting permission for the printing of the books.

At the same time, many printers were summoned to a hearing for the “scandalous” content of books they had printed. Two years later, on 16 June 1643, Parliament, which was at a disadvantage in the civil conflict between the two sides, issued a special ordinance under which the guild of printers and booksellers was in charge of licensing. Henceforth, she would exercise control over the forms to be published.

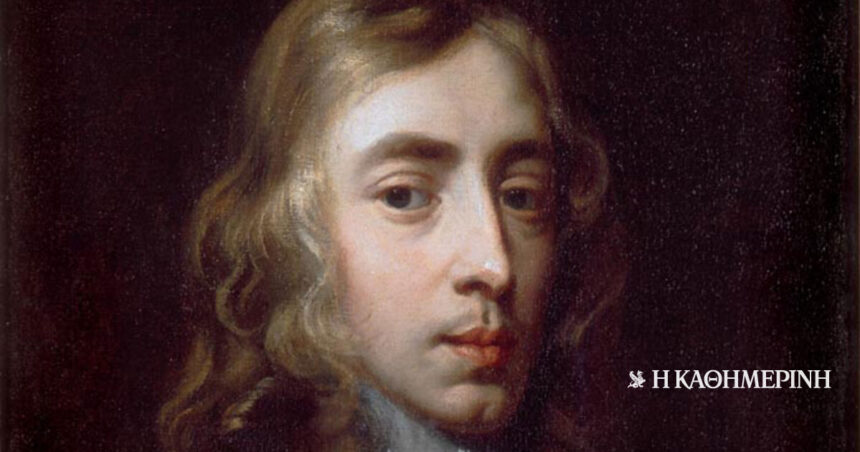

In this context, in August 1644 the “Doctrine and Discipline of Divorce” by the poet John Milton (who was in favor of divorce). Frustrated with the whole situation and although he supported Parliament against the king, Milton published on 23 November 1644 the “Areopagite”. It was an intervention addressed to the Parliament and requested “the freedom to print without permission».

The specific text, which received immediate and wide publicity, is actually a call to those in power to “see the light […]to escape from tyranny and embrace the truth”. However, it is worth noting that even in the case of Milton, who created a sensation with the Areopagiteas with the even more radical thinkers of the mid-seventeenth century, who continued to discuss “liberty,” “tender consciences,” and the “definition of blasphemy,” there was a difficulty in extending the claimed freedom of speech to the whole the spectrum of those who represented different perceptions.

Column editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigoni-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis