The slave ship “Zong” left the coast of Africa on September 6, 1781 transporting hundreds of slaves. Since the slave trade was highly profitable at the time, many slave ship captains carried more slaves than allowed, in order to maximize their profits.

So did “Zong” captain Luke Collingwood. Furthermore, due to the absence of favorable winds, the “Zong” accidentally sailed into an area of the Atlantic known as “the doldrums”, where it ran aground. During the voyage and the ship’s stoppage, disease and malnutrition caused – by November 29 – the death of 60 slaves and 7 of the 17 crew members.

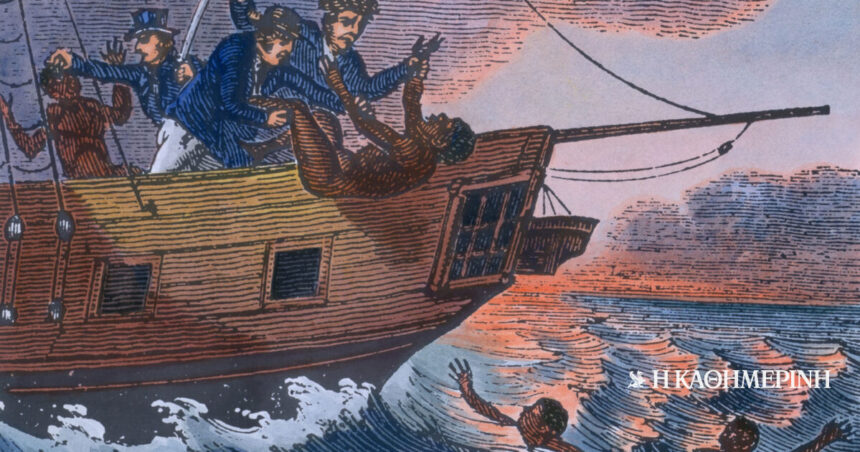

As water dwindled and the voyage lengthened by navigational error, the crew voted at one point to throw some of the human “cargo” into the sea, in order to ensure the safe delivery of the remainder. Thus, he threw 122 Africans into the sea: 54 on 29 November and 68 on 30 November and 1 December. It is noteworthy that 10 more jumped on their own, choosing suicide instead of murder.

The “Zong” eventually arrived at Black River, Jamaica with 208 slaves. On his arrival the owner applied to collect the security for the loss of the slaves, alleging that there was not enough water left in the ship to sustain both the crew and the…”human goods” (which was not the case: when he arrived in Jamaica he had a stock of 420 gallons of water). Although the underwriter, Thomas Gilbert, disputed his claim, the Jamaican court in 1782 ultimately ruled in favor of the owners. However, the case did not end there. The underwriters appealed a year later, an event that generated great public interest and the attention of abolitionists in Great Britain, including Granville Sharp.

The publicity surrounding the “Zong” massacre and the first trial led William Murray, Earl of Mansfield, and the Bench, Chief Justice in Great Britain, to order the retrial of the matter. The Earl of Mansfield, who presided, finally ruled in favor of the underwriters, as he believed that the cargo of slaves had been ill-treated, and that the captain ought to have provided for a proper quantity of water for each slave.

Sharp fought to have criminal charges brought against the captain, crew and owners, but without success. Attorney General for England and Wales John Lee denied murder charges. In fact, according to his words, it was not a case of murder, as people were not thrown into the sea but… “goods” – that is, nothing more than a… property! Therefore, for him, the case was no different from a case of throwing wood into the sea.

This massacre, as Sharp first characterized it, would gradually change the facts. In the years that followed, it became a benchmark for public awareness of the slave trade and the demand for the abolition of slavery. Four years after the trial, the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade was founded. In 1807 Parliament outlawed the Atlantic slave trade, while in 1833 slavery was outlawed throughout the British Empire.

Column Editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigoni-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis