The end of World War I found Italy in a critical situation. Even before the end of the war, the country was facing an extensive economic crisis: inflation and the increase in the prices of basic goods, as well as high rates of unemployment, due to the simultaneous mobilization of the Italian Royal Army, made life difficult for Italian citizens to such an extent that many analysts of the time considered that the country was on the verge of revolution, as early as the end of 1918.

Thus, the way was opened for the so-called “Red Decade” (1919-1920), a period characterized by mass strikes, demonstrations as well as attempts at self-management through the occupation of factories and farms. Within this climate, the socialist and anarchist movement emerged, through the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) and the labor unions. Indicatively, in 1919, 1,663 industrial revolts took place in Italy. However, this “revolutionary” movement began to lose its momentum, as by 1921 the industrial crisis led to mass layoffs and large reductions in wages.

But as a counterweight to the Italian workers’ movement, a group that enjoyed the support of industrialists and landowners took action: the Black Fascists (Fasci Italiani di Combattimento), later Benito Mussolini’s National Fascist Party (PNF). Coming himself from the socialist area, from which he was ostracized when he supported Italy’s entry into World War I, Mussolini led a militia named after the black shirt of its men’s uniform. With the material support of the industrial bourgeoisie, fascist militias began attacking unions and left-wing parties, as well as beating and murdering strikers, trade unionists, and socialist and communist militiamen.

Soon, the fascists’ violent imposition allowed them to control many areas of northern and central Italy, forcing unions and socialist associations to dissolve themselves within 48 hours, out of fear. On the other hand, the quarrels and the inability of the socialist leaders to act coherently, as well as the inaction of the police, which often openly supported the blacks, strengthened the fascist party. In fact, in August 1922, a general anti-fascist strike was organized by the socialists throughout the country. Mussolini stated that the Fascists would put down the strike themselves if the government did not intervene directly, portraying the Fascist party as the protector of law and order.

The dispute between socialists and fascists had reached the point of open street fighting in various Italian cities. Meanwhile, after the 1921 elections, in which the National Fascist Party had won 35 seats, it was impossible for Mussolini and Prime Minister Fakta to come to an agreement on the participation of the Fascists in the new government. Thus, the prospect of a coup d’état seemed increasingly likely. A decisive role was also played by the assignment by the prime minister to Gabriele D’Annunzio, a veteran of the First World War, poet, nationalist and main opponent of Mussolini, to organize a grand event to celebrate the victory in the war and the unification of Italy on the 4 November. Upon hearing this news, Mussolini decided to put into action his plan for the so-called “March on Rome”.

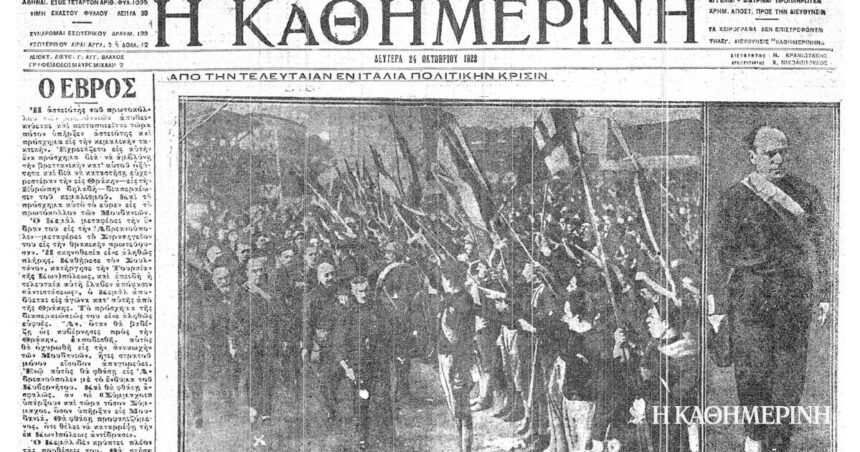

On October 27, nearly 30,000 blacks headed for Rome, intent on seizing power. Despite Fakta’s urgings to King Vittorio Emanuele to declare the city under siege, the king refused to sign the decree, leaving Mussolini virtually unimpeded. Vittorio Emanuele’s move has been interpreted by many as an attempt to avoid bloodshed, as an attempt to protect the monarchy, and even as part of a plan to weaken the fascists through their inclusion in the national government.

Finally, on October 30, the king handed over the premiership to Benito Mussolini, marking the beginning of a nearly twenty-year reign. In fact, despite the Fascist propaganda that presented the march to Rome as a conquest of power, it was a transfer of power within the Italian constitutional framework. After all, as it turned out later, Mussolini did not even participate in the march, but went to Rome by train.

Column Editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigone-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis