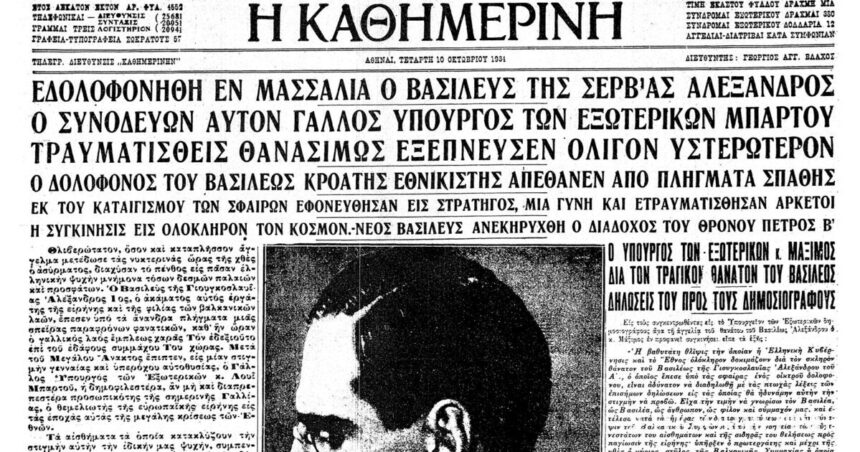

Shortly before 4 pm on October 9, 1934, the Yugoslav warship “Dubrovnik” docked in the port of Marseille. King Alexander I of Yugoslavia descends from it amid cannon fire and while the national anthems of Yugoslavia and France are being played. The crowd that had gathered at the harbor enthusiastically welcomed the king and a little girl offered him flowers. French Foreign Minister Louis Bartou accompanied the monarch in a black Delage cabriolet and, escorted by police forces, the two men began to move through the city’s cobbled streets.

Only a few minutes later, a man opened fire on the procession: King Alexander died instantly, Louis Bartou was wounded above the elbow, near the brachial artery, and the driver of the car was fatally wounded, as well as four bystanders. The killer, later revealed to be Vlado Chernozemsky, was wounded by a policeman’s sword and trampled by the crowd. Bartu was eventually taken to the hospital but died after bleeding profusely.

Alexander’s assassination came at a critical moment in the interwar period, but it was not really that surprising. Noting major victories in the Balkan Wars, Alexander, as regent of Serbia, proclaimed the establishment of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which was to evolve into Yugoslavia, on 1 December 1918. The formation of a new Slavic state had been decided in Corfu, where the Serbs had taken refuge to regroup during World War I, by Serbian and Croatian politicians last July. Thus they declared independence from Austria on October 29, 1919. The new state and its borders were recognized at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-20.

In 1921 Alexander became king and on June 28 he swore to preserve and uphold the new constitution of the state that later became known as Yugoslavia. It consisted of Serbia, Montenegro, Croatia, Slovenia, Dalmatia, Bosnia, Herzegovina and parts of North Macedonia. A few days earlier, he had married Princess Maria of Romania and tried to unify the various ethnic groups and political parties. But this proved particularly difficult: even on the day he was sworn in on the constitution, an assassination attempt was made against him. By the time of his death, he had survived 6 assassination attempts. In fact, he avoided public appearances on Tuesdays, as three members of his family had died on that day of the week. Coincidentally, October 9, the day of his murder, was a Tuesday.

The cause of these attempts can be traced to the dissatisfaction of the remaining ethnic groups towards the primacy of the Serbs in the central government, as well as to the discussions of Croatian autonomy. In 1928 violent protests broke out when elected Croatian representatives withdrew from parliament. The following year, a shooting incident in Parliament led Alexander to suspend the 1921 constitution and impose a military dictatorship known as the “regime of January 6”. Thus, the king was able to impose himself on the Yugoslav Communist Party, but at the same time, he paved the way for the creation of the Croatian Revolutionary Movement of the Ustaše (Ustaše, “rebel” in Croatian) under Ande Pavelić. When the movement was outlawed by the king, its leaders fled to Fascist Italy, where they operated secretly under the patronage of Benito Mussolini.

Meanwhile, Alexander intensified his efforts to unify his subjects and changed the name of the state to Yugoslavia on 3 October 1929. He outlawed any party based on ethnic, religious or local divisions and reorganized the state administration, standardized the legal system, school lessons and national holidays. He also included Yugoslavia in two alliances, the Little Entente (jointly with Czechoslovakia and Romania) and the Balkan Entente (with Greece, Turkey and Romania). A few years earlier, in 1931, he had created a new constitution giving himself executive powers and thus legitimizing the dictatorial regime.

As expected, Alexander had many detractors. The economic crisis had caused great popular discomfort, while many were those who were calling for a return to democratic institutions. It seems that Alexander was seriously considering the establishment of some form of parliamentary government, but he did not have time to effect any change.

Resentment against Alexander’s person was not limited to the Yugoslavs, but extended to Italy and Benito Mussolini himself. Throughout the 1920s, Fascist Italy vied with Yugoslavia on the grounds that it had not been given the lands promised to it in the Treaty of London of 1915. Its claims to parts of present-day Slovenia and Croatia were finally annulled at the Peace Conference of of Paris in 1919-20. In fact, in order to strengthen his position against Italy, Alexander entered into an alliance with France in 1927.

Thus, when in 1934 French Foreign Minister Louis Bartou invited King Alexander to talks in order to achieve a Franco-Yugoslav understanding, which in turn would open the way for Bartou to achieve an Italo-French reconciliation that could form a bulwark in Nazi Germany, it seems that Italy’s reaction was immediate. Count Ciano summoned Ande Pavelic to Rome and they hatched a plan to assassinate King Alexander, taking into account that the disorder inside Yugoslavia, combined with the death of the monarch, would be the right opportunity to secure what the Treaty had given Italy of London. The right man to carry out the operation was judged to be Vlado Chernozemski, a member of the Ustashe and the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization (EMEO), a Bulgarian anti-Serbian separatist organization. After all, he had already committed many political assassinations.

The moments shortly before and shortly after the assassination of Alexander and Barto were captured by a reporter filming the official visit of the Yugoslav king and are one of the first assassinations of a head of state to be caught on video. After Alexander’s death, his eleven-year-old son, Prince Petros, became king of Yugoslavia, with Prince Paul as regent. Peter became king 11 days before the German invasion, at which time he left the country. Ultimately, the Karageorgevich dynasty was declared deposed by Tito in 1946.

Column Editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigone-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis