In the now distant 2016, the famous international art fair Documenta it took place for the first time outside German borders, in Greece during the crisis. There was a lot of shame at the time for the manifesto of the exhibition, which examined the Greek case in a continuum “from dictatorship to neoliberalism”, while even anti-authoritarians of the Exarchies issued a manifesto against their treatment as natives by the northerners, who sought inspiration in the local “resistance”. However, the use of the wider space of the former ETA-ESA, now Freedom Park, for artistic events and speeches also caused controversy. Some then spoke of sacrilege, despite the approval of the competent Prisoners and Exiles Association. Has the reframing of space helped to understand the very defining concept of resistance today? Maybe yes, maybe not.

The post-revolutionary anti-dictatorship struggle was invested with sanctity from a very early stage, partially determining the immediate political developments. The Polytechnic itself, as a symbolic date, legitimized the first free elections on November 17, 1974. At the time, some spoke of Karamanli’s “hatching” of the anti-dictatorship student movement; however, the idea was vindicated not only by the moment, but also by the passage of time. PASOK itself was founded on the resistance parchments of two illegal organizations, the PAK and the Democratic Defense, despite the group deletion of the latter by Andreas for “factionalism”. Other places again failed to save the important anti-dictatorship action of their executives, such as the Center Union – New Forces, even though in the early days it had in its ranks the ultimate symbol of the struggle: Alekos Panagoulis.

The past and its “open accounts” overdetermined the political and public life of the country for years: the dictatorship, the tortures, but in the background also the Occupation, the Civil War, the explosion of the previously suppressed anti-fascist memory. People who resisted, exiled and imprisoned became MPs, ministers, journalists and academics, with a strong stigma of public intervention. Professors-gurus abroad, such as Nikos Poulantzas and Konstantinos Tsoukalas, would recognize in the explosion of young questioning of the late 1970s the positive and hopeful legacy of the anti-dictatorship struggle. On the other hand, Professor Dimitris Maronitis, who had been dismissed from the university, arrested and tortured by the junta, would stand alone against the creeping dangers of the unbridled left-wing student unionism, which was fed by the flesh of the Polytechnic rebellion. Could the Maronite speak so out of his teeth without being summarily unstuck if he himself had not reaped the laurels of resistance? Obviously not, and this tells us a lot about the value system of the time and the symbolic capital of the anti-dictatorship struggle in the post-colonial universe. However, the thorny issue of how many finally resisted was covered under the cover of the “Pallaic” mass resistance to the junta, in the context of the myth of the resistance people, whose neck yoke does not endure.

The thorny question of how many finally resisted was covered under the cover of the “Pallaic” mass resistance to the junta, in the context of the myth of the resistance people, whose neck yoke does not endure.

The glamor of resistance remained relatively intact until about the mid-1980s, despite the shift from collective hyper-politicization to individual hyper-consumption. Greece would register four prime ministers with anti-dictatorial action: two of PASOK with direct involvement in it (Andreas Papandreou and Costas Simitis) and two of N.D. (the elders Karamanlis and Mitsotakis) with indirect. Imprisonments, bombs, anti-junta statements, anti-dictatorship networks, campaigns to inform foreigners about the junta, the Council of Europe, are only part of this plural struggle against the regime, despite the chaotic differences. The same certainly applies to leaders of other parties (only from the leadership of the Coalition three eminently anti-dictatorial figures marched).

In the process, however, the anti-dictatorship action began to be overlooked or even completely misunderstood. In the 90s, the character of Spyros of the television “Unacceptable”, who “was at the Polytechnic”, indicated the gradual redemption of participation in the student movement in professional advancement and opportunistic love affairs. At the beginning of 2000, with the arrests of “November 17”, the collective destabilization of the so-called “dynamic” actions of resistance to the dictatorship took place, through a mechanistic interconnection of anti-dictatorial struggle and terrorism. While there have clearly been cases of people choosing this slippery slope, the perceived obsolescence of an entire generation has tarnished for good the formerly pristine halo of resistance. Resistance scrolls, insignia until then, began to be omitted from CVs.

Today, many of them have been covered by oblivion, while public history is called upon to “educate” new generations in relation to the past, with the 60s and 70s having their place of honor. Series such as “Wild Bees”, “Our Best Years”, and “The Beach” reposition the central question of resistance, highlighting also gray areas between passivity and combativeness, public and private, with torture giving and to take, as a representation now. Eight years after Documenta, the National Gallery took the visual sceptre, hosting a comparative exhibition entitled “Democracy”: The illustration of the rage of the resistance, but also of the trauma and mourning that coexist with it, contains something redemptive and that clearly visitors get it. Because the fragments of this resistance memory are ultimately part of our collective self-awareness. Half a century later, we can talk about them without uncritical romanticization, but also without cynicism and deprecation.

Mr. Kostis Cornetis is assistant professor of Modern History at the Autonomous University of Madrid.

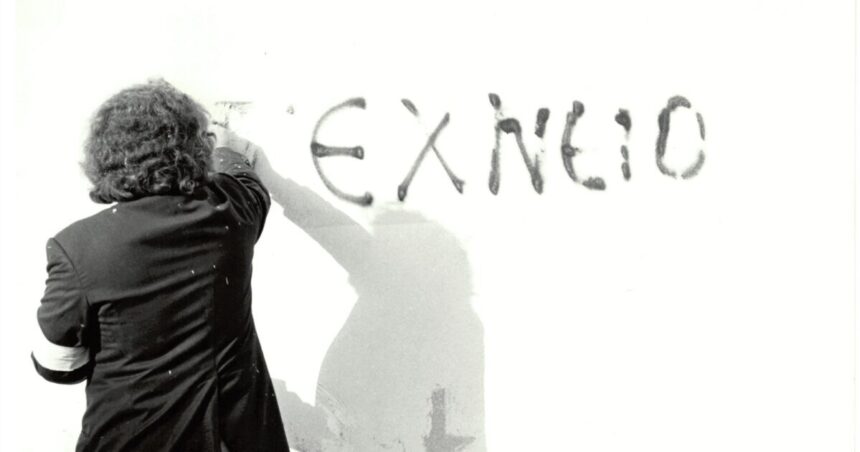

Central photo: In November 1974 the Polytechnic was already a slogan on the wall. Photo ASKI