The signing of the treaty of Kiucchuk Kainartzis, in July 1774, was not accompanied by a recession of the expansionist mood of of Russia against the Ottoman Empire. A constant goal of Russian foreign policy since the time of Peter the Great (end of the 17th – beginning of the 18th century), was the expansion to the South and the descent to the warm seas of the Black Sea and Mediterranean. To achieve this goal, after all, Russia used the radiation it exerted on the subjugated Orthodox populations of the Ottoman Empire, inciting them to revolt against the Ottoman authorities.

In the early 1780s, the Tsarina Catherine II expressed to the Habsburg emperor, Joseph II, her vision for the establishment of two states in Balkan Peninsula. These states were Dacia, which consisted of the Dominions of Moldavia and Wallachia, and the Greco-Byzantine state with its capital at Constantinople. She herself calculated that she would raise her grandson, Constantine, to the throne of Constantinople. This plan was never implemented as neither the Austrians took this proposal seriously, nor did Catherine herself believe that she could push the Ottoman Empire into disintegration.

In 1783, Russia annexed it Crimeawhich had been recognized as an independent state in 1774, expelled many of its Tatar inhabitants and laid the groundwork for its later expansion into the Balkans. Around these bases many Greeks settledseveral of whom engaged in trade. In 1787, Catherine made a triumphal tour of the region, which was rich in symbolism about her empire’s dominant role in the East.

With their ultimatum, the Ottomans demanded the evacuation of the Crimea and the annulment of the treaty of Kiucchuk Kaynartzis.

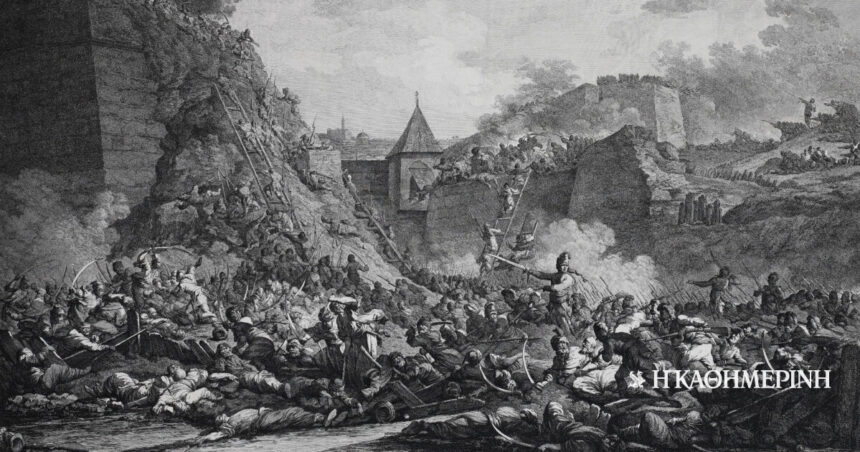

To these actions of the Russian side, the Ottomans responded with an ultimatum, demanding the evacuation of the Crimea from the Russians and the annulment of the treaty of Kuchuk Kaynardzis. A new Russo-Ottoman war broke out in 1787, in which he participated on the side of the Russians and Austriaas part of a secret treaty they had concluded. Military operations took place exclusively in the northern Balkans. Both the death of Joseph II and the threat of a Prussian invasion of Austrian lands forced Vienna to sign a separate peace with the Porte in 1791.

For their part, the Russians did not conduct operations with the same zeal they fought in the previous Russo-Ottoman war. Desiring an immediate end to the war, Russia ordered troops to head towards the Danube Delta, reaching as far as Ismail. The Gate then requested the opening of negotiations for the signing of a peace treaty. The two empires signed the peace treaty on January 9, 1792 in Iași, the capital of the Hegemony of Moldavia. Under the terms of the treaty, Russia confirmed its ownership of Crimea and annexed some areas on the northwestern shores of the Black Sea. In these lands, Catherine II founded it Odessaa city where many Greeks settled and played an important role in modern Greek history.

Column editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigoni-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis