World War I left behind a devastated Europe that bore little resemblance to the Old Continent of the Belle Époque. Even the victorious powers, the United Kingdom, France and Italy (which aspired to be among the great powers), emerged from the war shattered. At the time of the negotiations for the signing of the Versailles peace treaty, it seemed very likely that the United States, an emerging great power, emerging from the war materially intact and greatly strengthened economically compared to Europe, would bring order to the chaos in Europe the weakened European countries.

After the end of the Great War, as World War I is often called, the map of Central, Eastern and South-Eastern Europe changed radically. The dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian, Russian, German and Ottoman Empires led to the establishment of new states, such as Czechoslovakia, Poland, Finland, the Baltic States, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and the doubling of others, like the Great Romania of the interwar period. These states were intended to act as buffer states against German revisionism and Soviet influence.

In Southeast Europe, the more than doubling of the Romanian kingdom and the creation of a large Yugoslav state overturned the pre-war intra-Balkan balance vis-à-vis Greece. All three states, however, belonged to the camp of the winners of the war. Their main concern was the preservation of territorial integrity and internal consolidation.

The restoration of the new borders in Europe did not become an easy task, especially in areas where the population was not homogeneous ethnically, linguistically and religiously. In the context of the multinational empires of the pre-Great War era, populations in many areas lived in mixed communities, making it difficult to demarcate the new states. One of the affairs that preoccupied the diplomacy of the time was the question of Carinthia on the Austro-Yugoslav border.

According to the principle of the self-determination of the peoples, of which the American president G. Wilson was an advocate, both the Slovenes and the Germans of Carinthia, Styria and Carniola had the right to national restoration. Gradually, a hostile climate began to be created between the two ethnic groups in these areas on the occasion of whether or not to join the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. The phenomenon of the action of Yugoslav paramilitary groups, which intimidated the German residents, was not rare. During an armed attack by these groups in January 1919, which became known as “Bloody Marburg Sunday”, about ten Germans were killed. The Great Powers intervened to defuse extensive conflicts between the two ethnic groups, which were supported by Austria and the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes respectively.

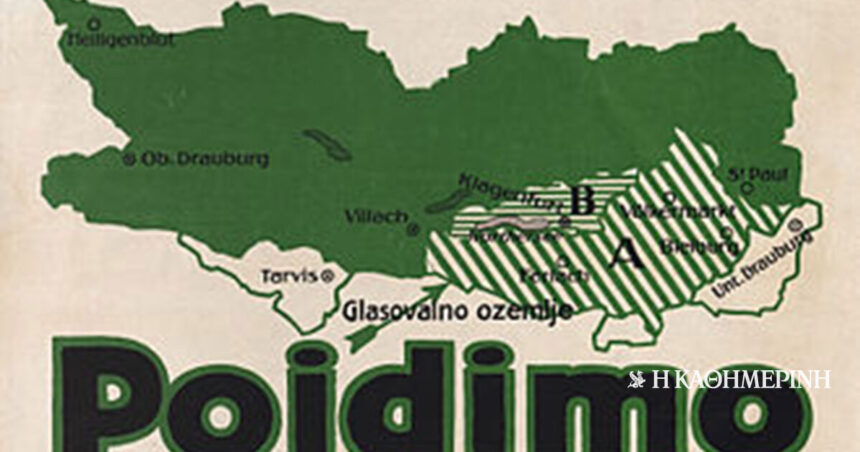

Based on the terms of the Treaty of St. Germanus (1919), some areas of Carinthia joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, while for others it was decided that their fate would be determined by a referendum. In the run-up to the referendum, both the Austrians and the Yugoslavs carried out intense propaganda in order to convince the population of Carinthia, of which according to a 1910 census 70% spoke Slovene as their main language, to choose to join their own state.

In the referendum of 10 October 1920, 59.1% of the population of Carinthia chose to join Austria, even though the majority of the population was of Slavic-Slovenian origin. It seems that the Slovenes of Carinthia preferred to remain in a relatively developed state and not to break their economic and social relations with the rest of Carinthia with Klagenfurt as its capital.

Column Editor: Myrto Katsigera, Vassilis Minakakis, Antigoni-Despina Poimenidou, Athanasios Syroplakis